In a Bloomberg Businessweek interview last month, Megaupload founder Kim Dotcom talked extensively about copyright and business models. Dotcom, who has been criminally charged in the United States in relation to copyright infringement, was asked by the interviewer if he “believed in copyright.” Dotcom replied that he did, but argued that he did not believe in “copyright extremism” – a term he used to describe extended delays in content distribution, which often result in content reaching foreign markets months after it is released in the United States.

According to Dotcom, the solution to such “extremism” is a worldwide studio-run streaming platform rather than, as the Washington Post’s Brian Fung described it, “letting Netflix play the middleman.” Essentially, “extremism” is another way of saying that piracy is more a business model problem than a policy problem. Expensive and controversial copyright enforcement would be more efficiently supplanted with different business practices.

But this raises an obvious question: if there is a better way of doing things, why aren’t things done that way? The answer is that different stakeholders bear the costs of different solutions. Moving to worldwide online distribution entails risks borne mostly by industry stakeholders, who would be abandoning a time-honored content distribution strategy referred to as “windowing” or “release windows.” On the other hand, the risks of the current windowing model are known, and the costs of this model fall at least in part on taxpayers.

What Are Content Release Windows?

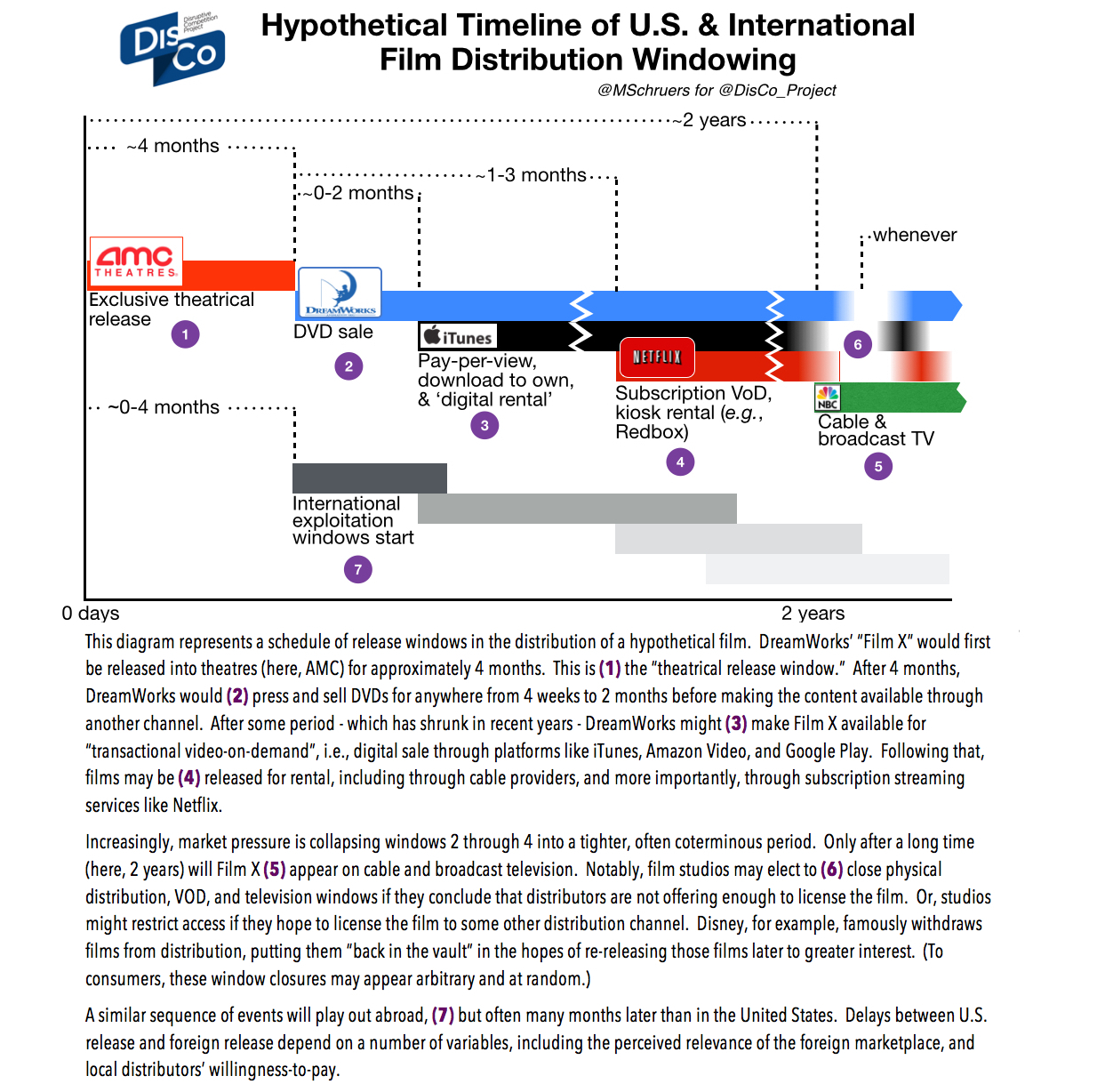

The traditional approach to distribution of film and some other content involves selective release through different and often exclusive channels, in different markets, for different times. This means content may only be available through a particular channel for a period of time. This period is dictated by the license, and it may occasionally be mandated by law. As a result, the availability of a given piece of digital content often appears to consumers to change arbitrarily.

The most sacrosanct window has always been that of initial theatrical exhibition. This is the time frame during which newly released films are exhibited in traditional movie theaters. Over time, the length and nature of this window has changed, and it has generally become shorter. As data from the theater owners’ trade association shows, the theatrical exhibition window has contracted over the last decade, but it still stands at roughly 120 days in the United States, and can be far longer in other markets.

After the theatrical exhibition window, studios traditionally undertake DVD sales (sometimes described with the term of art, “sell-through”), and in some cases download-to-own (alternatively, “electronic sell-through” or “EST” or “transactional video-on-demand”). Following the purchase window, films may be licensed for digital rental and pay-per-view, on platforms such as iTunes, Google Play, and Amazon Instant Video, followed by subscription video-on-demand (SVOD), and then other outlets like cable television, airlines, hotel pay-per-view, and so on. One should not overlook that the actual length of any given window will vary based on the film, the market, the licensing practices of the distributor in question, and the willingness-to-pay of the licensee in question, which contributes to the unpredictability of content availability.

Typically, as later windows (such as broadcast television, airlines, and hotel pay-per-view) are opened, distributors may withdraw their content from earlier windows. Thus, films tend to disappear from online SVOD platforms, such that other prospective licensees may have their own exclusive access to a film for a period of time.

Who Cares About Content Release Windows?

The strategy of windowing has long been practiced because it is believed to maximize revenue opportunities for a given film. By giving successive distribution channels exclusive rights to the work, a film distributor aims to extract maximum revenues from licensees in each channel. Certainly, there are exceptions to the traditional model. For example, this year the dystopian Snowpiercer was available by VOD before it was even available in theaters, and trade press viewed the gamble as paying off. Yet this is the exception to the rule. Conventionally, film distribution focuses on sequential maximization of returns in each of the major windows in large markets. Like a line outside a restaurant or club implies the venue is in demand, having a queue of prospective licensees waiting for their turn to distribute a work in a specific window in a specific market is perceived as the best way to maximize the value of the work.

Even if film distributors were to reject the conventional wisdom of windowing, those windows are jealously guarded by their respective sectors. The theatrical exhibition window is particularly so. When the Weinstein Brothers announced in September 2014 that they would distribute a sequel to the 2000 hit Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon simultaneously via Netflix and IMAX theaters worldwide, movie theater chains swiftly circled the wagons and announced a boycott of the Weinsteins’ film. (A large number of IMAX theaters are operated by the major theater chains, hamstringing the Weinsteins’ distribution efforts.) As the incident showed, theaters presently have sufficient leverage to defend their exclusive release window. Subsequent release windows are heavily defended as well, including by the studios themselves. As a Warner Home Video representative explained in 2012 said when announcing consumers would have to wait twice as long to find Warner films on Netflix,

“Since we implemented a 28-day window for subscription and kiosk, we have seen very positive results with regard to our sell-through business…. One of the key initiatives for Warner Bros. is to improve the value of ownership for the consumer and the extension of the rental window… is an important piece of that strategy.”

To be clear, “value of ownership for the consumer” is a euphemism for “consumer willingness-to-pay.” The longer a consumer must wait before they can watch a movie on their Netflix subscription, the likelier that consumer is to pay for a DVD. Or, unfortunately, pirate the movie. That additional piracy notwithstanding, those “positive results” ensure that studios want to maintain the sanctity of the “sell-through window,” just as movie theaters want to maintain the theatrical exhibition window.

The result? Dotcom’s idealized worldwide streaming platform for now exists only in fantasy or outside of the law, because moving to such a marketplace bodes poorly for too many constituencies in the distribution chain. The result is a fragmented marketplace that pits convenience against copyright compliance.

The Effect of Release Windows Abroad

For consumers outside the major distribution markets, content availability can be scarce. Just as films are windowed by distribution channel, they are effectively windowed by jurisdiction as well. Foreign market windows often lag considerably behind their U.S. counterparts, as commercial exploitation in smaller, less lucrative markets is de-prioritized to focus on major markets like North America and Europe. Outside the United States, therefore, consumers may hear the buzz of a film’s U.S. release in ads, news, and social media, but upon attempting to purchase the film discover that it will not be available in their market for months, if ever.

As a result, distribution sectors in smaller markets have an interest in protecting their window even though it may be out of sync with what is happening in large markets. This can result in lobbying for statutory protection. In Dotcom’s own New Zealand and other countries, for example, the importation of lawfully produced DVDs is prohibited for months after the release of the film to ensure that local theater owners maintain some period of exclusivity. Otherwise, consumers might be buying DVDs before theaters even have a chance to exhibit the film.

Policymakers openly concede this is to consumers’ detriment. As of 2012 in New Zealand, a survey revealed that nearly half of all films were released for theatrical exhibition in the country 3 months or more after first being made commercially available in a foreign market. By prohibiting the importation of DVDs, legislatures attempt to shore up their domestic theater owners, who might otherwise lose out to home viewing. In essence, these sectors have succeeded in lobbying policymakers to legislate their business model.

To be fair, this phenomenon is not unique to film. As discussed in previous DisCo posts, numerous industries have attempted to insulate themselves from disruption by persuading lawmakers to prescribe their exclusive industrial role in public laws, including auto dealers and beer distributors.

Why Content Release Windows Drive Piracy

What differentiates content distribution from cars and beer is that when consumer needs go unmet, resorting to unlawful avenues is relatively easy. For this reason, windowing has been widely criticized as contributing to piracy, and “leaving money on the table.” Empirical evidence bears that out. Content producers are not unaware of this data; their calculus is that the revenues attributable to aggressive windowing (and avoiding friction with their distributors) exceed losses associated with piracy.

The problem is that costs associated with piracy are not the full universe of costs resulting from windowing. Windowing alienates consumers and arguably undermines respect for copyright in countries that receive content late. Additionally, copyright enforcement costs public money. Certainly, private actors enforce copyrights (which still imposes burdens on the courts), but increasingly public law enforcement and federal officials play this role. In the United States, so many government officials are devoted to IP enforcement that in 2008 the White House created a new czar to coordinate them all.

These government resources could be allocated elsewhere — or back to taxpayers. Different distribution strategies might reduce the costs of government piracy enforcement, but because the costs are largely borne by the public, and not the content distributors, there is little incentive to minimize them. If a particular distribution strategy is perceived to produce a net increase in the rightsholder’s return after accounting for increased piracy, then the fact that the increased piracy also imposes costs on taxpayers is irrelevant.

This is what economists call a “negative externality.” A negative externality is a“spillover”: a situation where an actor does not bear the full cost of the economic decisions. Classically, economists and lawyers will use pollution as an example to explain externalities. (The Wikipedia entry for externality suggests a number of other examples, as well as examples of positive externalities.) A factory might pollute the air while making widgets, which depresses home values in a nearby town. The factory’s widget profits outweigh the unpleasantness of pollution, but (unless regulated) the factory doesn’t bear the cost of lower real estate values in the town. As long as the factory does not have to pay for all the costs of its manufacturing, its decisions may be individually economically rational, even if they may be inefficient when viewed across the large economy. Insofar as we conceptualize high-infringement distribution strategies as a type of economic risk, then this problem could also be studied as a form of moral hazard, but that is beyond the scope of this post.

Possible Solutions

At this point, the policy question turns to what – if anything – should be done to address the externality. Whole treatises have been devoted to this question. Traditionally, economic models consider whether a policy should be implemented to “internalize” negative externalities. In other words, who should bear the cost? Is the factory entitled to pollute or is the nearby town entitled to clean air? Is a rightsholder entitled to a business model that imposes a greater burden on government resources, or should taxpayers be relieved of that expense? If the policy preference is that taxpayers should bear the expense, it may nevertheless be more efficient for taxpayers to subsidize the adoption of a different business model. Indeed, subsidies in the film industry are quite common, although not without controversy.

If the policy preference is that the externality should be internalized, then the producer of the cost is made to bear that cost. In the pollution example, the factory may be compelled to compensate nearby residents, or it might be required to pay into a clean-up fund. In the content distribution example, compensation might involve repayment for government resources expended on attributable piracy, perhaps based on a user-fee model that various government agencies already have. If the windowed release distribution model generated more revenue than the costs it incurs, it would continue, taxpayers would be made whole, and the externality would be “internalized.” If that behavior produced less private value than the public cost, however, then businesses employing release windows would likely switch to alternate distribution strategies that impose less costs on the taxpayer.

The post The Public Costs of Private Distribution Strategies: Content Release Windows as Negative Externalities appeared first on Disruptive Competition Project.